Last Updated on February 4, 2023 by Nathaniel Tower

If you’re planning to submit anything to a literary magazine or publisher, it’s essential to play by their rules. Some publishers claim to receive ten thousand submissions per month. While you may think that adding a unique touch is necessary to make your manuscript stand out, your deviation from the guidelines will more likely result in your work instantly being thrown out.

Follow the Guidelines

When it comes to submitting to a literary magazine, the most important thing you can do is follow the guidelines. Of course, by “guidelines” I mean a wide range of things, not just the rules about formatting and submission method described on the magazine’s website. The guidelines of a literary magazine include both stated and unstated rules you need to follow when you submit. Failing to follow just one of them might mean you never get out of the slush pile.

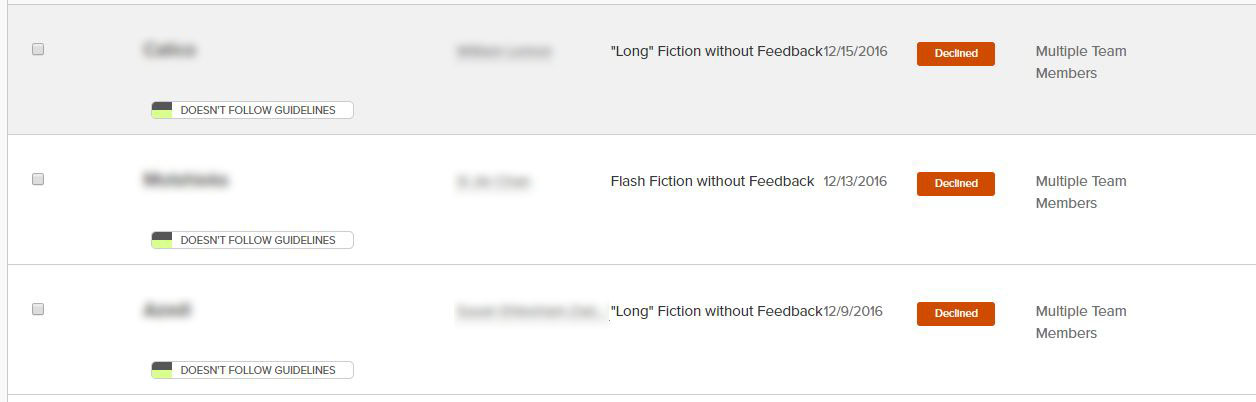

When I was Managing Editor of Bartleby Snopes, we had a label in Submittable for “Doesn’t Follow Guidelines.” If the submission violated any of our stated guidelines, we added the label and rejected the piece immediately. We used this label a lot. A quick look at our Submittable data shows that over 6% of submissions did not follow our basic guidelines, and this doesn’t include the many submissions that blatantly ignored our content guidelines. However, we often gave writers a second chance and told them they could submit the piece again if they updated the submission to follow the guidelines, but most publications won’t give you this chance.

I like to break down guidelines into five categories: Length, content, format, method, and information. It might be easy to say that “content” is the most important of these. After all, good writing should trump the fact that you didn’t double space. However, your great story might never be read if you don’t follow the conventions the magazine lays out for you.

Here is an overview of each category:

Length

Most literary magazines will provide either a maximum word count or a word count range. Some magazines may allow flexibility, but others will have a very firm word count. In general, it’s wise to stick within the length requirements. If the publication has a 3,000 max word count and your story is 3,005 words, then cut 5 words before submitting your story.

The best way to figure out if a magazine will consider your story that’s 300 words over their max is to look at the archives and see if they always stick to the length requirements. While some places like McSweeney’s Internet Tendency are very precise about their length preferences (although you should probably take their preference for 742-word pieces with a grain of salt), other magazines are a bit of a mystery.

A good habit to follow when you are submitting is actually reading some of the work a magazine has published. Reading what they publish gives you a sense of what they really want. If they are calling for 1-3000 words and you don’t see anything less than 1000 words on the site, then maybe you don’t want to send in your 25-word masterpiece. Occasionally you will find a magazine with no length restrictions. Again, browse the contents and see what lengths they prefer. If all their stories are under 2000 words, don’t send in your 15,000-word epic.

Content

Content is arguably the most important aspect about your submission. After all, even if you follow all the other rules, you’ll still get rejected if your story is bad or doesn’t fit. Content refers to the style and aesthetic of your writing. It’s also the type of writing (prose, poetry, etc), the genre, the subject, and so much more. The amount of direction a magazine explicitly gives you regarding the content you should submit will vary. Some magazines give specific information regarding what they want to see. Others may give you a list of things they don’t want to see. Many publications will keep it vague and tell you to read the work they’ve published to get a sense of their aesthetic.

If the guidelines specifically tell you what not to send, then don’t send it. A lot of publications list things they specifically don’t want to see. Things that often make that list: stories about writers, stories about zombies, stories that are racist, sexist, or homophobic, stories that have any type of child abuse, etc. I hope you aren’t writing any of these things anyway, but if you are, please don’t send them to publishers who specifically tell you they don’t want to see them (hint: NO ONE wants to see these topics).

As with length, the best way to determine the types of stories a particular venue publishes is to actually read the stories in that publication. Almost every literary magazine provides free stories. If the only way to read the magazine is to buy a copy, then buy a copy. If you don’t want to buy a copy of the magazine, then you probably don’t really want to be in that particular publication.

Choosing the right content to send a publisher is the most difficult part about submitting, but it’s worth taking the extra time to figure out what they really want. If you don’t make a serious attempt to learn the aesthetic of a magazine, then you are just wasting everyone’s time. Ultimately, you want to submit a piece that is a good match for that magazine’s tastes (but that doesn’t mean you should try to be a copycat–avoid sending a story that is exactly like something they already published).

Format

Following the requested format won’t guarantee acceptance, but it might ward off instant rejection. Some magazines will immediately reject a piece that doesn’t conform to their guidelines. Some publications may be very specific in format requirements, while others may not care at all. If you want to play it safe, always prepare your story in standard manuscript format. You can always make adjustments as needed to meet the particular quirks of a magazine. As a writer, I’ve seen format guidelines that seem rather petty, but if you aren’t willing to play along, then don’t bother playing at all. Format guidelines may include:

- Font

- Text size

- Margins

- Spacing

- Hard returns

- Indentation

- Headings/headers/titles/page numbers

- Identifying/contact information

Getting a manuscript in the proper format generally only takes a few minutes, and it shows the editors that you actually read their guidelines. This can go a long way.

Method

There are two main aspects to the method of submission. The first is the medium you use to submit (email, snail mail, submission manager, form on site). If the publication uses Submittable, don’t send an email. If they only accept snail mail, don’t send an email. Never contact an editor to ask if you can submit your work using a different way.

The second aspect of method refers to what you send. If you are emailing, do you send it as an attachment or in the body of the email? If you need to use an attachment, what type of file should you use (RTF, DOC, DOCX, PDF, etc)? Do whatever they say, no matter how archaic it sounds. Again, if you don’t want to put forth the effort to use the proper method, then don’t bother submitting.

You should also pay attention to whether or not the publication allows simultaneous submissions or multiple submissions. When a publication forbids simultaneous submissions, you should do your best to respect this and not send the same work to other publications. Similarly, if they say no multiple submissions, then don’t send ten stories at the same time.

Information

The final aspect of your submission is often optional and can include a range of items: a cover letter, a bio, an author photo, and more. Be sure to follow the magazine’s policy and include any additional information they want. When it comes to literary magazines, your bio and cover letter rarely make a difference. Many editors don’t even look at these items before reading your submission. However, it’s always polite to at least include a brief cover letter that thanks the editors for taking the time to read your work—and make sure you don’t address the letter to the wrong magazine (this happens a lot more than you might think).

The Final Word on Submissions

If you are serious about having your work published, especially in “prestigious” venues, then you need to invest time into the submission process. Yes, it can be a pain and rather time-consuming to follow all the different guidelines, and some magazines do make some strange requests. As with almost anything else, when it comes to submitting your work, you will probably get out of it what you put into it. If you send out a lot of rushed submissions without doing your research, you will probably end up with a big stack of rejections. If you put time and effort into submitting your work, then you will likely walk away as a published author (eventually).

Do you stick to the submission guidelines? Share your tips for following (or breaking) the rules in the comments.

So I have a few essays produced as a result of writing class. I have never tried to submit, I have been told they’re great and funny. They deal with stories of being a child immigrant and are meant to be humorous-roughly 3000-5000 word length pieces. Do you have a suggestion as to what publications I should try to

Submit to first ? I also have a few pieces there more serious, they deal

With tragedies and crimes. I’m not ready to share any of those pieces nowC but at some point I will

I attribute any nonsense to voice messaging

Unfortunately I can’t recommend any publications for those particular pieces off the top of my head. I would recommend using Duotrope or The Submission Grinder to find a good place to submit. Duotrope is a bit more robust, but The Submission Grinder is completely free to use. Both of them will help you find a venue that might work.

In terms of formatting guidelines, the templates provided on Shunn’s site actually follow a bit of bad word processing form, or at least the novel version does. For instance, using line breaks to push the content onto a new page or further down the page is not cool. It creates problems when the content changes and I imagine becomes a formatting headache for editors/publishers. He also manually indents the beginning of each paragraph which is entirely too much work for me and I’m going to forget to do it constantly. I understand that he provided macros in the templates to do at least some of it, but that’s still more work than necessary.

So I ended up changing some of his styles to do that all automatically, in addition to assigning the chapter numbers a place in the document outline so it’s easier to bounce around the document. I want to concentrate more of my energy on writing a shitty novel than I do on basic formatting. It should be easier to format to meet submission guidelines later as well.

Great points about his format. To be fair, I think he created that back in the typewriter days. Either way, your modifications make a lot of sense. Now get back to that shitty novel. I’m looking forward to reading it some day.